Ghost Towns

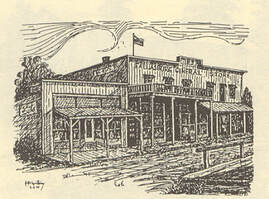

This is the corner of Main and Broadway c. 1885 looking northeast.

Note the Perrin and Perrin Livery sign on the corner.

The land where the livery stood is now where the post office stands.

Note the Perrin and Perrin Livery sign on the corner.

The land where the livery stood is now where the post office stands.